What is heartworm disease? Heartworm disease is a serious and potentially fatal disease in pets (dogs, cats and ferrets) in the United States and many other parts of the world caused by a parasite called Dirofilaria immitis. Heartworms belong to the same class of worms as roundworms. In fact, they look a bit like roundworms, but that is where the similarity ends. Heartworms live primarily in the large vessels connecting the heart and lungs. Heartworms primarily affects pets like dogs, cats (yes, cats) and ferrets, but they have been identified in other species such as wolves, coyotes, foxes and sea lions. In fact, wild foxes and coyotes living near urban areas serve as carriers of the disease. It is important to note heartworm disease does carry public health significance and has been positively identified in people, but the incidence of heartworm infection in people is especially rare.

The dog is a natural host for heartworms, which means that heartworms that live inside the dog mature into adults, mate and produce offspring. Untreated, adult heartworms increase in number. Heartworm disease causes permanent damage to the heart, lungs and great vessels, and can affect the dog’s health and quality of life long after the parasites are gone. For this reason, prevention is by far the best option, and treatment—when needed—should be administered as early in the course of the disease as possible.

Heartworm disease in cats is very different from heartworm disease in dogs. The cat is an atypical host for heartworms, and most worms in cats do not survive to the adult stage. Cats with adult heartworms typically have just one to three worms, and many cats affected by heartworms have no adult worms. While this means heartworm disease often goes undiagnosed in cats, it’s important to understand that even immature worms cause real damage in the form of a condition known as heartworm associated respiratory disease (HARD). Moreover, the medication used to treat heartworm infections in dogs cannot be used in cats, so prevention is the only means of protecting cats from the effects of heartworm disease.

How do animals get infected with heartworms?

The mosquito plays a paramount role in the heartworm life cycle. Adult female heartworms living in an infected dog, fox, coyote, or wolf produce microscopic baby worms called microfilaria that circulate in the bloodstream. The microfilariae enter a mosquito when it feeds on an infected animal. Over a period of 10-14 days, the microfilariae develop and mature and possess the ability to infect other animals. When an infected mosquito bites another dog, cat, or susceptible wild animal, the infective larvae are deposited onto the surface of the animal’s skin and enter the new host through the mosquito’s bite wound. The larvae continue to mature and migrate to the heart within 65 days, where they grow into adults. The time from when an animal was bitten by an infected mosquito until adult heartworms develop, mate, and produce microfilariae is about 6-7 months in dogs and 8 months in cats. (Remember this – it is important when we talk about diagnosis.)

Once mature, heartworms can live for 5 to 7 years in dogs and up to 2 or 3 years in cats. Because of the longevity of these worms, each mosquito season can lead to an increasing number of worms in an infected pet. Severely infected dogs can have dozens of heartworms in their hearts and vessels. Interestingly, there are more than 70 different species of mosquito that can transmit heartworms.

In the early stages of the disease, many dogs show few symptoms or no symptoms at all. The longer the infection persists, the more likely symptoms will develop. Active dogs, dogs heavily infected with heartworms, or those with other health problems often show pronounced clinical signs.

Signs of heartworm disease may include a mild persistent cough, reluctance to exercise, fatigue after moderate activity, decreased appetite, and weight loss. As heartworm disease progresses, pets may develop heart failure and the appearance of a swollen belly due to excess fluid in the abdomen. Dogs with large numbers of heartworms can develop a sudden blockage of blood flow within the heart leading to a life-threatening form of cardiovascular collapse. This is called caval syndrome, and is marked by a sudden onset of labored breathing, pale gums, and dark bloody or coffee-colored urine. Without prompt surgical removal of the heartworm blockage, few dogs survive.

Signs of heartworm disease in cats can be very subtle or very dramatic. Symptoms may include coughing, asthma-like attacks, periodic vomiting, lack of appetite, or weight loss. Occasionally an affected cat may have difficulty walking, experience fainting or seizures, or suffer from fluid accumulation in the abdomen. Unfortunately, the first sign in some cases is sudden collapse of the cat, or sudden death.

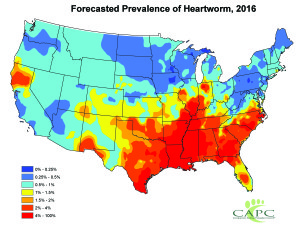

Stray and neglected dogs and certain wildlife such as coyotes, wolves, and foxes can be carriers of heartworms. Mosquitoes blown great distances by the wind and the relocation of infected pets to previously uninfected areas also contribute to the spread of heartworm disease (this happened following Hurricane Katrina when 250,000 pets, many of them infected with heartworms, were “adopted” and shipped throughout the country).

The fact is that heartworm disease has been diagnosed in all 50 states, and risk factors are impossible to predict. Because infected mosquitoes can come inside, both outdoor and indoor pets are at risk.

For that reason, the American Heartworm Society recommends that you “think 12:” (1) get your pet tested every 12 months for heartworm and (2) give your pet heartworm preventive 12 months a year.

Heartworm disease is a serious, progressive disease. The earlier it is detected, the better the chances the pet will recover. There are few, if any, early signs of disease when a dog or cat is infected with heartworms, so detecting their presence with a heartworm test administered by a veterinarian is important. The test requires just a small blood sample from your pet, and it works by detecting the presence of heartworm proteins. Some veterinarians process heartworm tests right in their hospitals while others send the samples to a diagnostic laboratory. In either case, results are obtained quickly. If your pet tests positive, further tests may be ordered.

Annual testing is necessary, even when dogs are on heartworm prevention year-round, to ensure that the prevention program is working. Heartworm medications are highly effective, but dogs can still become infected. If you miss just one dose of a monthly medication—or give it late—it can leave your dog unprotected. Even if you give the medication as recommended, your dog may spit out or vomit a heartworm pill—or rub off a topical medication. Heartworm preventives are highly effective, but not 100 percent effective. If you don’t get your dog tested, you won’t know your dog needs treatment.

Cats. Heartworm infection in cats is harder to detect than in dogs, because cats are much less likely than dogs to have adult heartworms. The preferred method for screening cats includes the use of both an antigen and an antibody test (the “antibody” test detects exposure to heartworm larvae). Your veterinarian may also use x-rays or ultrasound to look for heartworm infection. Cats should be tested before being put on prevention and re-tested as the veterinarian deems appropriate to document continued exposure and risk. Because there is no approved treatment for heartworm infection in cats, prevention is critical.

No one wants to hear that their dog has heartworms, but the good news is that most infected dogs can be successfully treated. The goal is to first stabilize your dog if they are showing signs of disease, then kill all adult and immature worms while keeping the side effects of treatment to a minimum.

Here’s what you should expect if your dog tests positive:

Confirm the diagnosis. Once a dog tests positive on an antigen test, the diagnosis should be confirmed with an additional—and different—test. Because the treatment regimen for heartworm is both expensive and complex, your veterinarian will want to be absolutely sure that treatment is necessary.

Restrict exercise. This requirement might be difficult to adhere to, especially if your dog is accustomed to being active. The more severe the symptoms, the less activity your dog should have.

Stabilize your dog’s disease. Before actual heartworm treatment can begin, your dog’s condition may need to be stabilized with appropriate therapy.

Dogs with no signs or mild signs of heartworm disease, such as cough or exercise intolerance, have a high success rate with treatment. The severity of heartworm disease does not always correlate with the severity of symptoms, and dogs with many worms may have few or no symptoms early in the course of the disease.

Approximately 6 months after treatment is completed, your veterinarian will perform a heartworm test to confirm that all heartworms have been eliminated. To avoid the possibility of your dog contracting heartworm disease again, you will want to administer heartworm prevention year-round for the rest of his life.

What if my cat tests positive for heartworms?

Like dogs, cats can be infected with heartworms. There are differences, however, in the nature of the disease and how it is diagnosed and managed. Because a cat is not an ideal host for heartworms, some infections resolve on their own, although these infections can leave cats with respiratory system damage. Heartworms in the circulatory system also affect the cat’s immune system and cause symptoms such as coughing, wheezing and difficulty breathing. Heartworms in cats may even migrate to other parts of the body, such as the brain, eye and spinal cord. Severe complications such as blood clots in the lungs and lung inflammation can result when the adult worms die in the cat’s body.

Here’s what to expect if your cat tests positive for heartworm:

Diagnosis. While infected dogs may have 30 or more worms in their heart and lungs, cats usually have 6 or fewer—and may have just one or two. But while the severity of heartworm disease in dogs is related to the number of worm, in cats, just one or two worms can make a cat very ill. Diagnosis can be complicated, requiring a physical exam, an X-ray, a complete blood count and several kinds of blood test. An ultrasound may also be performed.

Monitor your cat. If your cat is not showing signs of respiratory distress, but worms have been detected in the lungs, chest X-rays every 6 to 12 months may be recommended. If the disease is severe, additional support may be necessary. Your veterinarian may recommend hospitalization in order to provide therapy, such as intravenous fluids, drugs to treat lung and heart symptoms, antibiotics, and general nursing care. In some cases, surgical removal of heartworms may be possible.

Preventives keep new infections from developing if an infected mosquito bites your cat again.

Whether the preventive you choose is given as a pill, a spot-on topical medication or as an injection, all approved heartworm medications work by eliminating the immature (larval) stages of the heartworm parasite. This includes the infective heartworm larvae deposited by the mosquito as well as the following larval stage that develops inside the animal. Unfortunately, in as little as 51 days, immature heartworm larvae can molt into an adult stage, which cannot be effectively eliminated by preventives. Because heartworms must be eliminated before they reach this adult stage, it is extremely important that heartworm preventives be administered strictly on schedule (monthly for oral and topical products and every 6 months for the injectable). Administering prevention late can allow immature larvae to molt into the adult stage, which is poorly prevented.

There are significant tangible benefits of heartworm preventive worthy of mention. A number of currently available preventive medications are also effective against certain internal parasites. Some of the products are better than others, but all typically offer some activity against commonly encountered internal parasites. Most have the ability to control roundworm and hookworm infections. Select few can also control tapeworm and whipworm infections and contain products effective against external bugs such as fleas, ticks, and ear mites. That said, it’s important to realize that no single product will eliminate all species of internal and external parasites. I suspect the day will come when we have available a more comprehensive product, but that day is not here. Consult your veterinarian to help determine the best product for your pet.

Dr Scotty Gibbs is with Hilltop Animal Hospital in Fuquay-Varina (www.hilltopanimalhosp.com), and the only local practice that’s now using laparoscopic surgery.

References: The American Heartworm Society